Imagine a chemical so resilient that it doesn’t break down in the environment, stays in your body for years, and is linked to serious health problems like cancer, liver damage, and immune system disruption.

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a group of synthetic chemicals that have been widely used since the mid-20th century in various industries. They are popular in manufacturing due to their unique properties. However, growing evidence has revealed significant health and environmental risks associated with PFAS exposure, prompting regulatory bodies to take action.

But despite all the evidence, environmentalists, lawmakers, and chemical manufacturers are finding this seemingly simple task very difficult to legislate on.

What Are PFAS Chemicals?

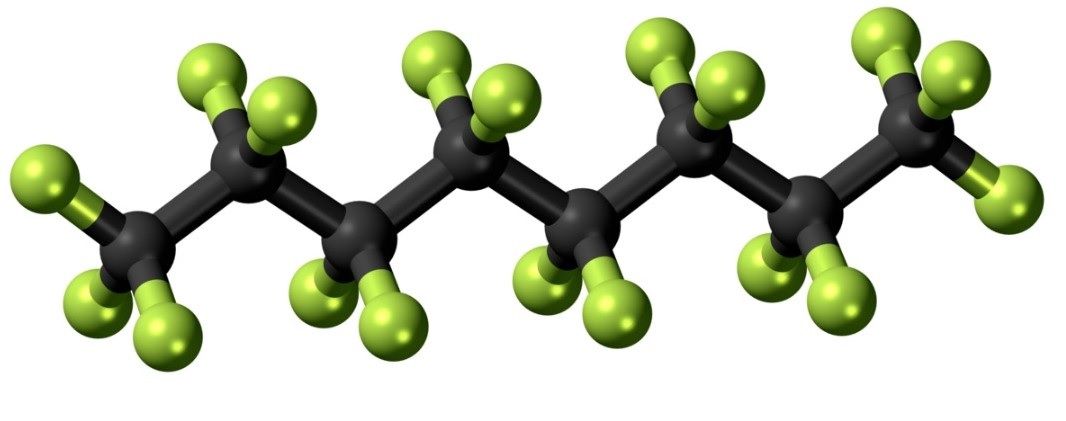

PFAS is a collective term for thousands of synthetic chemicals that share a common characteristic: a chain of carbon atoms bonded to fluorine atoms, which creates a strong and stable molecular structure. This structure is responsible for their water- and oil-repellent properties. PFAS have been used in a wide range of products, from non-stick cookware and waterproof clothing to firefighting foam and food packaging.

Yet while PFAS have many uses, they also have many drawbacks. Most notable of these is that they do not easily break down in either the environment or the human body. This has left them with the alternative name of ‘forever chemicals,’ with researchers even finding that they accumulate in soil, water, and living organisms.

While PFAS are valuable in industrial and consumer products, they come with serious health and environmental risks. Studies have linked PFAS exposure to a variety of health problems, including cancer (particularly kidney and testicular cancers), liver damage, immune system suppression, fertility problems, and developmental issues in children.

In response, countries are taking steps to regulate PFAS. However, these efforts have been fragmented, with regulations focused on specific chemicals rather than a comprehensive ban on the entire class.

In the European Union, for example, PFAS are subject to regulation under the REACH (Registration, Evaluation, Authorization, and Restriction of Chemicals) framework. Some PFAS compounds, such as perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), have therefore been banned or severely restricted in certain applications. The EU has also begun investigating the possibility of restricting all PFAS as a group, recognizing that the persistence and toxicity of these chemicals poses a global problem. However, due to the large number of PFAS variants, implementing a ban on the entire class remains a complex task.

In the United States, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has also taken steps to regulate PFAS. The EPA has set drinking water standards for certain PFAS compounds and is working to develop further regulations. However, currently, only six PFAS are regulated by the federal government. As a recent Newsweek report notes, “Those requirements were only rolled out last year when former President Joe Biden ordered municipal water systems to remove six synthetic chemicals that are present in the tap water of hundreds of millions of Americans.”

“We are one huge step closer to finally shutting off the tap on forever chemicals once and for all,” announced Michael Reagan, who was head of the EPA Administration when the legislation was passed.

However, environmentalists argue that stopping these chemicals is just not that easy.

“There's no guarantee that all other PFAS will be filtered out,” explains Jamie DeWitt, the director of Oregon State University's Environmental Health Sciences Center. But why is this?

The Problem of Banning PFAS Individually

One of the key challenges in regulating PFAS is that the chemical industry has produced thousands of different variants. While individual chemicals like PFOA and PFOS have been targeted for bans or restrictions, new PFAS chemicals are continuously being developed to replace the banned substances. This means that regulatory agencies must individually evaluate and ban each variant, creating a cumbersome and slow process.

“The problem is that the industry keeps inventing new ones,” says Erik Olson, a senior strategic director at the Natural Resources Defense Council. “Every time you get rid of an old one, or you control an old one, a bunch of new ones are coming at you.”

This is because, like the EU, the US has focused on banning individual substances rather than addressing the entire class of chemicals. This piecemeal approach has left significant gaps in the regulation of PFAS, allowing new varieties of these chemicals to enter the market without adequate oversight. Moreover, many PFAS compounds are similar in structure but may have slightly different properties, which complicates the task of regulation.

“It's like playing whack-a-mole,” explains Olson.

The absence of a blanket ban on all PFAS compounds allows the chemical industry to continue producing substances that share many of the dangerous characteristics of their predecessors.

“There are hundreds [of PFAS] that are not regulated, and there's no stoppers on industries from creating new ones,” says Ronnie Levin, an instructor in Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, who is well known for her work in removing lead from US drinking water. “These are all manufactured [chemicals], so it's easier to tweak it, because they made it up.”

It is this slow, regulatory response, to a fast-paced chemical industry which is infuriating environmentalists and health watchdogs.

PFAS chemicals have provided valuable benefits to various industries, but their persistence and toxicity have led to significant health and environmental risks.

While progress is being made to limit PFAS exposure, the future of these chemicals depends on finding safe alternatives and developing effective clean-up strategies. Until then, it seems that legislation will always be playing ‘catch-up’ with the new products that the chemical industry produces.

“The only way to really control this is by regulating PFAS as a class,” concludes Olson. “[Until then] I call it the toxic treadmill because that's kind of what we're running on.”

Photo credit: Freepik, Freepik, Wikimedia, Hit-BG, & Highlander