Many on the continent are in awe of why the British public have remained so keen on voting against their best economic interest. Certainly, national pride and a belief that the ‘British Spirit’ can overcome is a key part of the Brexiteer mood.

This is the second part of a two-part analysis of how the chemical industry will cope with the effects of the UK leaving the EU. You can find the first part here; The Fate of the UK Chemicals Industry Outside of the EU Part 1.

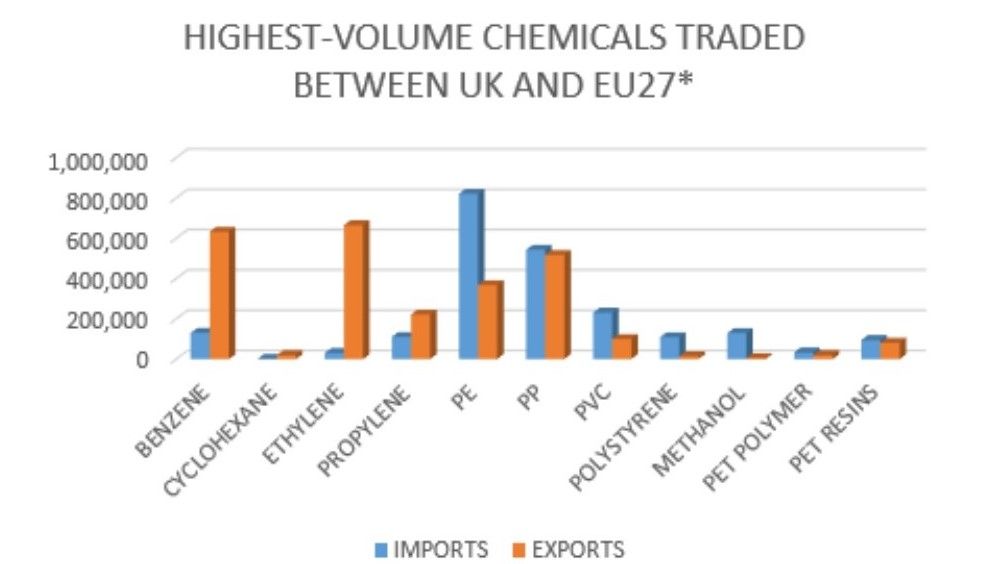

This is despite the fact that historically, British economic success has been based on successful international trade. It is something that is crucial to the success or failure of the UK chemicals sector. As a report in the New Statesman highlights, “63 per cent of the industry’s exports went to the EU in 2017 and 73 per cent of its imports came from there. In a sector with very tight profit margins, seemingly small tariffs — like the average of 4 per cent that the EU levies on other countries around the world — would have a disproportionate affect.”

Consequently, economists and chemical business leaders are more likely to look at the black and white of trading chemicals across borders than British Bulldog bravado. Noting that the importance of international trade is written into the legal text and policy code of agreements with acronyms such as REACH, IED, BREF, and CLP.

Perhaps the problem lies in how little the public and many politicians know about how international trade operates.

“It’s very hard to understand,” says Philip Aldridge, the chief executive of the North East of England Process Industry Cluster (a trade body for chemicals businesses on Teesside). “I struggle with it myself. So public consciousness just isn’t there.”

The fear is that without public understanding of the issue, the importance of freely trading chemicals between the UK and EU is no longer important at the ballot box.

“Historically we’ve been a bit frustrated that we haven’t had the ear of the public,” agrees Stephen Elliott of the UK’s Chemical Industry Association (CIA). “People tend to think of us as a smelly pollutant industry. But basically, society and manufacturing don’t work without chemicals.”

Public ignorance of the challenges facing chemical companies in the UK means that so much of the country also remains unaware of the threat to jobs should an EU/UK trade deal not be agreed by the end of 2020.

“The chemicals and processing industry is massive for Teesside,” explains Andy McDonald, a Labour MP from the North East of England. It employs directly in the region of 8,000 people. Downstream that extends to 32,000. The incomes of those directly engaged in the industry are good. The average is around £40,000 a year as opposed to a regional and median income of around £24,000. So, these are good jobs.”

Employment that could be at risk if free trade between UK chemical companies and those in Europe is not allowed to continue.

“Tariffs on raw materials coming in and finished products going out would completely decimate any element of profitability,” McDonald adds. “Multinationals will assess whether or not individual plants are core to their European and global trade or not. My fear and apprehension is that those companies will no longer regard the UK as core.”

Inside the EU trading bloc, the UK chemical industry is a big part of a major economic powerhouse. Without a deal to stay as a part of that machine, the UK chemicals sector could become side-lined.

To highlight this point, chemical industry insiders highlight the case of Ineos (whose Monaco-based, billionaire boss, Jim Ratcliffe, is a fervent Brexiteer) which has relocated its Acrylonitrile plant out of the UK. While the loss of 145 jobs from Teesside to Saudi Arabia will not destroy the British economy, the effect of such a closure on a heavily integrated industry will take a toll.

“For CF Fertilisers, that’s the loss of a customer who takes 40 per cent of their by-product,” notes Alex Cunningham, a Labour MP based in the heart of the UK’s chemical sector. “The integrated nature of the industry means everything depends on everything else.”

Evidence perhaps of the slippery slope that awaits the UK chemicals sector without a deal.

In the meantime, chemical companies live in uncertainty. Research by Bloomberg Economics estimated in January 2020 that, “The economic cost of Brexit has already hit 130 billion pounds ($170 billion), with a further 70 billion pounds set to be added by the end of this year. That’s based on the damage caused by the U.K. untethering from its Group of Seven peers over the past three years.”

And with every passing month without a deal this cost is rising. Failure to reach an agreement for smooth trade could be even more expensive.

“If we don’t get a good trade deal the whole lot will go with the result of thousands of job losses,” says Aldridge. “It’s not an assumption. It’s not a scare story.”

Photo credit: Chemicalindustryjournal, Tass, Bpf, Thenational, Thetimes, Icis, Chemistryworld, & Chemwatch, Pixabay