The sourcing of raw materials follows certain trends. Demand for recycled substances is growing, as is the need for products with a low climate change impact, while the discovery of nanomaterials such as graphene and carbon nanotubes is also causing huge changes.

Now a team from Norway are predicting that the next big thing in the sourcing of raw materials will be recycled lithium.

Recent years have seen massive growth in the consumer electrical device market, where the development of lithium-ion batteries for mobiles and tablets has led to a new sector for supplying raw materials to the battery industry.

Lithium, however, is quite rare, and can only be found in small pockets of the Earth’s crust.

One of the biggest sources of demand for lithium is in electric cars. But despite being full of valuable raw materials, electric vehicle owners must pay to have their car batteries recycled!

This is because current methods for recycling lithium are so inefficient that there is barely any profit in doing so.

At present, most European electric car batteries are dismantled and sent for recycling in Belgium, Germany, or Canada. During this process, the raw material is incinerated to recover the nickel and copper, but this means that the lithium is lost.

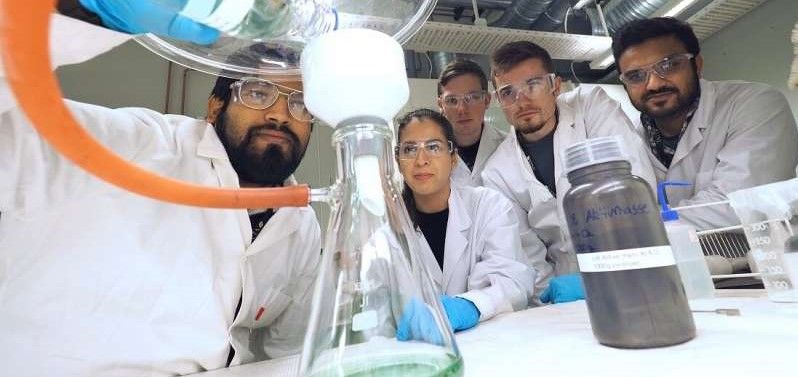

Researchers from the Norwegian Institute of Science and Technology (NTNU) have now collaborated with Norwegian industry to change this situation and plan to make lithium recovery a worthwhile practice.

“Our goal is 100 percent recycling of lithium from electric car batteries,” says Sulalit Bandyopadhyay, a postdoctoral fellow at NTNU's Department of Chemical Engineering.

While this may sound like a niche industry, it could be big business in Norway which has a growing number of EVs on the road.

As the Norwegian government website points out, the country, “… has decided on a national goal that all new cars sold by 2025 should be zero-emission (electric or hydrogen). As of May 2018, there are 230, 000 registered battery electric cars (BEVs) in Norway. Battery electric and plug-in hybrid vehicles together hold a 50 % market share.”

Many of these cars are only now reaching the end of their lifespans with little incentive offered to recycle the lithium in the batteries.

The goal for increased EV usage is encouraged by higher taxes for petroleum powered vehicles which funds investment in electric vehicle infrastructure. This includes, “… more than 10,000 publicly available charging points and more than 1,500 cars can fast-charge at the same time.” EV owners in Norway also enjoy a 25% luxury tax reduction on their purchase and zero import taxes. This makes it cheaper in Norway to buy a battery powered VW Golf than a petrol driven VW Golf.

In addition to this, EV owners pay reduced parking costs, zero road tax, and zero road and bridge tolls.

While these efforts are creating a cleaner way to drive, it could also lead to a potential problem when so many new EV batteries become old. As the technology journal Phys.org report notes, “EV batteries normally have a lifetime of around 10 years, which means that the vast majority of these batteries still work. But in a few years there will be enough electric cars that the number of used batteries in Norway will rise sharply. Then there will also be more money in recycling. It's important to get the technology and equipment in place before that time.”

The researchers hope to be able to efficiently recycle the lithium from EV batteries using hydrometallurgy. A technique that dissolves the desired raw material in water and then precipitated. An approach that is already used for extracting zinc and nickel.

Based on this, the team will develop a process that recovers lithium, nickel and cobalt from what is called a black mass.

As the Phys.org report explains, “Black mass is a black powder that consists of the materials in the battery that are active, meaning the material that is found on the electrodes. The composition of the material varies depending on what kind of chemistry is used to make the battery cells, but typically contains nickel, cobalt, manganese, lithium and carbon.”

“It is important to look at the recycling of metals other than lithium,” notes Bandyopadhyay. “In a few years, completely different metals might be used in car batteries than at present.”

Such is the political and business enthusiasm for the project that Swedish researchers and industry have also become involved, with plans to establish full-scale recycling for the entire Scandinavian EV battery market.

One of the largest investors is Norsk Hydro ASA, a company that specialises in metal recycling, which fully believes that this is the start of something significant. “We want this project to lay the foundation for a new, exciting industry related to the recycling of used electric car batteries in Norway,” says Norsk Hydro’s chief engineer, Christian Rosenkilde. “Norway's unique position with the availability of these batteries gives us an excellent starting point.”

It is the changing nature of Norway’s EV market that is prompting the investment. As the economies of scale begin to work, recycling lithium can become a worthwhile business.

“Recycling lithium from EV batteries isn't financially profitable yet, but a Bloomberg report shows that this will change in the next few years,” explains Bandyopadhyay. Adding that, “We plan to launch a pilot plant in 2024, and a full-scale plant in 2027.”

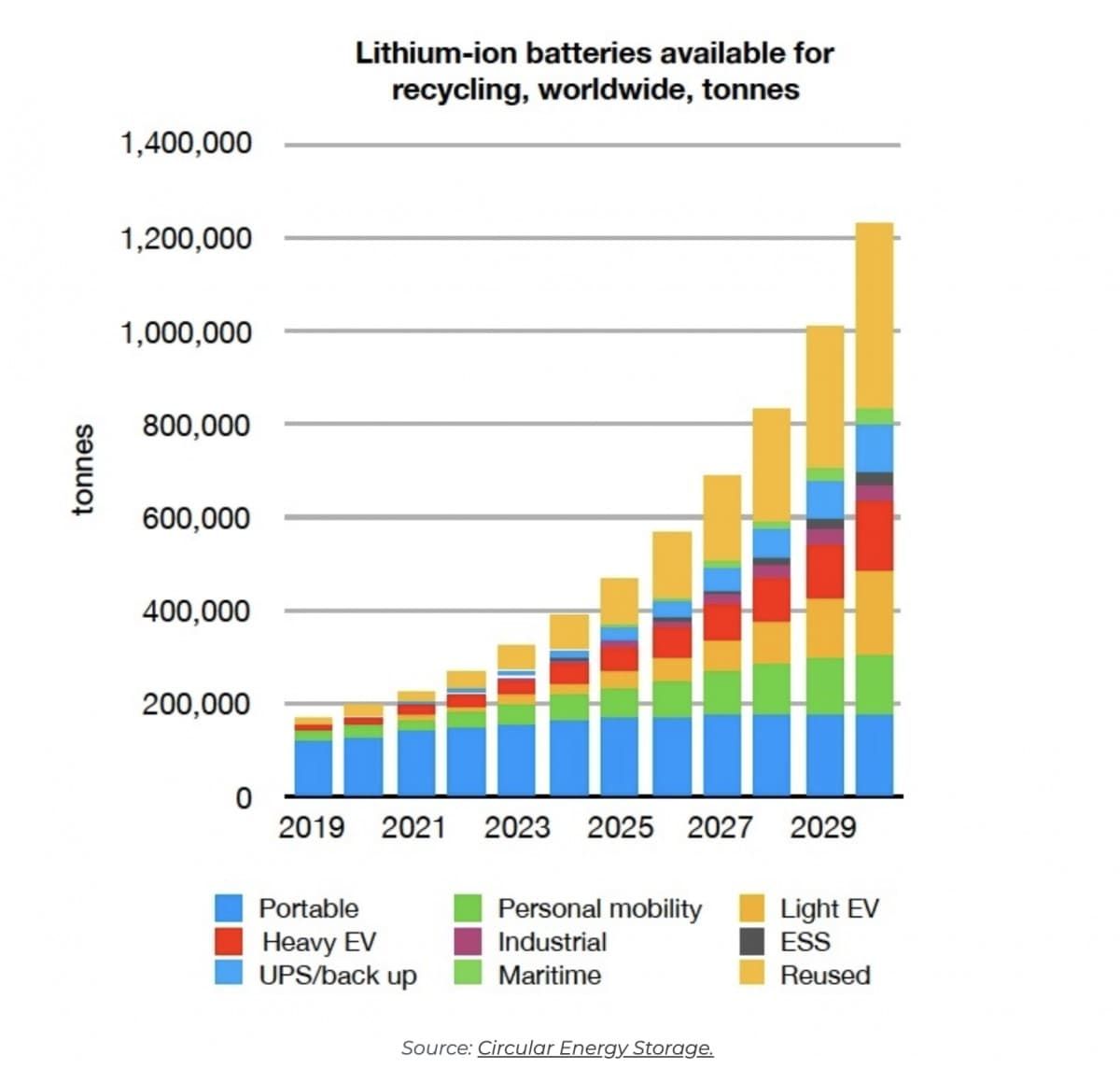

Certainly, there is money to be made in the battery industry.

As the energy journal OilPrice notes, “China alone is forecast to generate around 500,000 tonnes of battery waste by 2020, a number that would hit 1.2 million tonnes per year by 2030, when considering global consumption.”

Adding that the London-based Circular Energy Storage, “sees a profitable business on battery recycling…[where] recycled material and second life batteries can generate a market worth more than $6 billion, based on current metal prices.”

This offers even greater potential to the Norwegian project, with the force of both national research institutions and the automobile and recycling industries, assisted with government funding, the possibility of establishing a new and profitable lithium recycling industry is good. In fact, the entire project will be a huge boost not only to the prospects of the electric vehicle industry, but also in outlining the best way to source raw materials in the future.

Photo credit: Electrek, Phys.org, EEnews, qcostarica, OilPrice, & Envirotecmagazine