Russia’s invasion of Ukraine created an unprecedented energy crisis.

It has made and lost fortunes. It has re-invented industries. It has re-formed diplomatic ties.

It is a geopolitical event that has changed world energy markets for a generation, if not forever.

Despite its wealth, the EU was most exposed to the repercussions on energy prices and supply, with European Union nations importing almost half their natural gas and third of their oil from Russia.

This has threatened to freeze its population and made some of its most important industries question both their energy sources and raw material supplies. Industrial chemical producers have been in the eye of this storm. Although, only recently have the published profit reports shown the extent of the damage.

Sabic for example, announced a “quarterly profit slump of 94%”, while BASF reported a proposed slash of 2,600 jobs as profits fell to “€5.4 billion from 6.9 billion in 2022, which was down 11.5% from 2021.” Albeit part of this drop in business was due to a general slowing of the global economy.

Conversely, energy companies have been presenting bumper profits to their shareholders as prices soared following the invasion. CNBC, for example, reporting that, “Altogether, the five Big Oil companies reported combined profits of $196.3 billion,” way up on the previous year, with France’s Total Energies even doubling its windfall.

In the same way that different sectors of the economy have been affected differently, so too have different countries.

According to Marcello Estevao, the global director of macroeconomics, trade and investment at the World Bank, energy importers such as Pakistan and Bangladesh have been “hanging on, but can’t afford to pay as much for on spot cargoes as wealthy European nations.”

This has led to fears that some nations may not be able to pay for all their energy needs, causing widespread blackouts, rationing, or government budget cuts.

“Energy-importing countries have been caught out,” Estevao notes. “Some will probably be forced into austerity.”

On the other hand, energy exporters, such as Angola or Nigeria have been enjoying larger governmental incomes. “Hydrocarbon exporters in the Middle East and Africa received a boost from higher energy prices,” adds Estevao. “Especially those with spare capacity to raise production.”

Although, some of this has been partially offset by the increased costs of maintaining expensive petrol subsidies.

The worst hit nations are those like Ethiopia and Kenya, who both import oil and have petrol subsidies in place.

Most surprisingly of all, is that the country hardest hit by the energy crisis has been Russia.

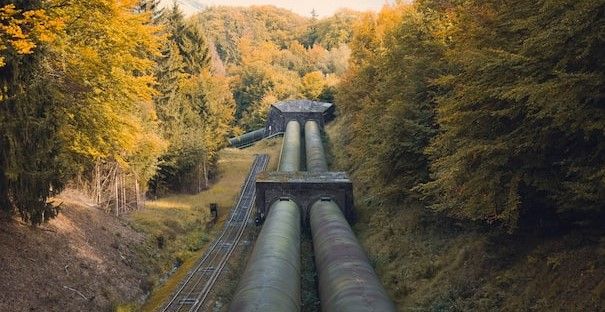

In January 2023, Russia was still exporting 8.2 million barrels of oil per day to world markets, down only 160,000 barrels per day on pre-war levels. However, most of this is now shipped to Asia as Europe has removed its dependency on Russia for energy and chemical feedstocks.

Russian oil revenues have dropped 36% according to the International Energy Agency compared to a year earlier.

“If there’s been anything more effective than Kyiv defending itself, it’s been the full-frontal assault on Russia’s energy business,” says Yale Professor Jerry Sonnenfeld in a recent interview with DW. “Russia has become an economic afterthought. Two thirds of the Russian economy was coming from the energy business, we now know that nobody needs Russia’s gas.”

Equally astonishing, is that the EU has been able to survive the worst of winter, all while transforming its economy away from Russian fossil fuels.

“This time last year 86% of Europe’s gas was coming from Russia,” adds Sonnenfeld, “now it’s less than 7% and it could go to zero.”

This transformation was possible through the construction of six mega-energy conversion terminals in Germany as well as two pre-existing facilities in the Iberian Peninsula that are able to receive and convert liquified natural gas. “They were built so fast, you would have thought they were Chinese companies building them,” jokes Sonnenfeld. “LNG has turned out to be an enormous source of energy as it can be shipped. So, now Norway and the US provide individually more than Russia did at its peak, with Algeria and others also adding to the equation the price has fallen 70% in the past year. So, it has become more and more affordable.”

However, the greatest change to energy markets, and the largest benefit of the war in Ukraine, has been the increased investment into renewable energy sources.

While in the short term, many countries have been re-starting, older, de-commissioned coal-fired power plants to make up for the shortfall in gas, in the long-term governments are seeing the need for energy security. For many that means renewable sources such as wind, wave, and solar.

The result, the International Energy Agency reports, is that, “the world will add as much renewable power in the next five years as it did in the last 20”.

With the deadline fast approaching to stop the disaster of climate change, maybe Putin’s invasion came at just the right time.

Photo credit: American Public Power Assoc, Ian Simmonds on Pixabay, Quentin de Graaf, Kwon Junho on Unsplash, Solen Feyissa, & Arvind Vallabh