The media attention on the war in Ukraine has naturally focused on the casualties, refugees, and geo-political situation. Further analysis has also been given on the war’s affect on stock markets, currency values, and national debt management, and when it comes to raw material supplies, most of the conversation has been on gas, oil, and other central feedstocks.

However, the supply of raw materials for the manufacture of semiconductors will be one of the conflict’s greatest impacts.

Also known as integrated circuits or transistors or computer chips or microchips, semiconductors have been a revolution to the modern world. They are the tiny electronic switches which do all the ‘thinking’ in computers. As technology progresses towards the Internet of Things, semiconductors can be found in countless manufactured products, such as phones, cars, TVs, tablets, fridges, dishwashers, and almost anything else which is electrical.

Currently, the global supply chain is experiencing a severe shortage of these tiny blocks of silicon, cobalt, and copper which sit inside almost every electronic device on the planet.

Much of the deficit was caused by delayed extraction and processing of feedstocks as well as lost production time during the COVID pandemic. However, the problem was also exacerbated by car manufacturers cutting orders for semiconductors in early 2020 as vehicle sales plunged. When demand returned far quicker than expected the semiconductor industry had already shifted production lines to meet market needs for other applications.

Just as supply was getting close to matching demand, the war in Ukraine has thrown another spanner into the supply of the raw materials used to make these vital parts.

As Pallavi Singh, VP at Super Plastronics Pvt Ltd (SPPL), made clear even before fighting had begun, “The global semiconductor chip shortage, which has only marginally been covered, may worsen due to the current Russian-Ukraine tension.”

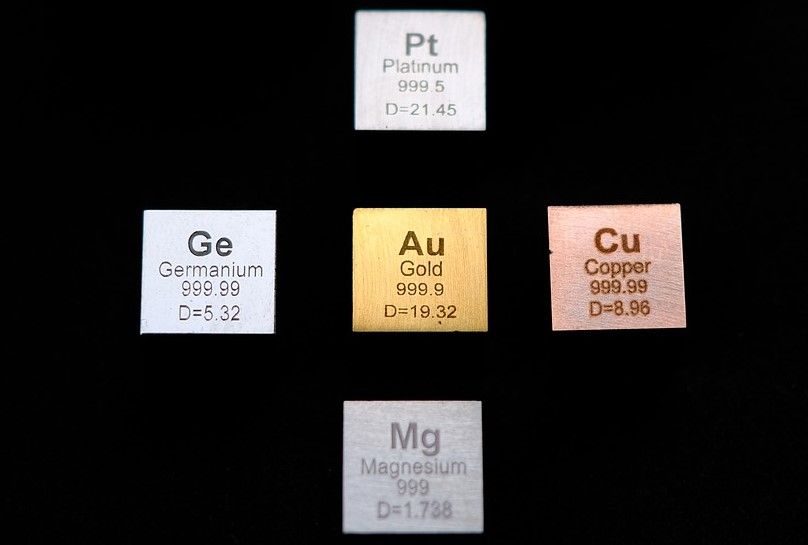

It is a point supported by Per Hong, a senior partner at consulting firm Kearney, who recently stated in an interview with CNBC, “The U.S. chip industry heavily relies on Ukrainian-sourced neon.” This is in addition to the palladium and platinum used in semiconductors that Ukraine also exports.

Palladium is used in memory and sensor chips, while neon gas is used for etching circuit designs. Russia is home to 45% of the global supply of palladium.

Russia is another major producer of neon, palladium, and platinum, so there are concerns that sanctions from the West may also inhibit those raw material exports used to make microchips. For example, the CNBC report states that, “About 90% of neon, which is used for chip lithography, originates from Russia, and 60% of this is purified by one company in Odessa.” Adding that, “Alternative sources will require long term investments prior to being able to supply the global market.”

“Both Ukraine and Russia also play a pivotal role in the global semiconductor supply chain,” notes Prabhu Ram from the Industry Intelligence Group, CMR. “Ukraine is a significantly important source and supplier of raw materials, including, for instance, semiconductor-grade neon used in semiconductor manufacturing.” Adding that, “While the semiconductor chip industry may not feel a direct heat from the war, the upstream raw material suppliers providing these gases, and enabling the chip companies, will face pressure.”

“We're in the worst of it now,” says Pat Gelsinger, CEO at Intel. “Every quarter, next year we'll get incrementally better, but they're not going to have supply-demand balance until 2023.”

Evidence of the shortage shows desperately low stock levels, with one survey reported by Business Insider showing that, “Of more than 150 firms found supplies had fallen from an average of 40 days' worth in 2019 to just five days in late 2021.”

Without turning on the TV or tablet, most of the world would be oblivious to the war raging on around Kyiv. However, the longer the war continues, the ability to supply the raw materials that make those devices will become harder and harder.

Photo credit: Johannes Plenio from Pexels, Jonas Svidras on Unsplash, Pixabay, & Mkaylani.