The coronavirus, the pandemic, and the lockdown has got the chemical industry thinking: How to improve and maintain security and stability in supply chains?

The simple answer it seems, is to diversify. To connect with multiple suppliers from different regions and countries so that if another virus strikes, or geopolitical relations turn cold, or if a trade war ignites, then alternative suppliers will instantly be on hand.

This is a great solution. Certainly, for those trading in basic chemicals or simpler feedstocks, such as the raw materials for plastic production.

But what should chemical companies and manufacturers do when their supply sources are limited?

How can a producer of rare earth magnets diversify when almost all rare earth supplies come from a single source?

The biggest challenges for sourcing rare earth elements first became evident 11 years ago, when prices rocketed due to fears over supply stability.

Realising the importance (and therefore growing value) of rare earth minerals for the electronics, automotive, and manufacturing industries, investors flocked to fund new mining projects. At the same time, governments also began supporting these projects as they became aware of the strategic significance of rare earths for the production of military hardware, satellites, and advanced communication systems.

Over the next few years, market forces and the end of the price spike meant that many projects soon folded.

As the commodities news service Argus Media, explains, back in 2009 there were about 300 rare earth mining projects around the world. “But you can count the number of western projects that made it through to production on the fingers of one hand. And only one of these managed to transition downstream from mining ore to large-scale commercial rare earth processing and separation to provide the raw material for magnets. Today, Australian mining firm Lynasis the only large light rare earth oxide producer outside China, second only to Chinese state-controlled industry group Northern Rare Earth.”

That has left 95% of the world’s rare earth element extraction and processing in Chinese hands.

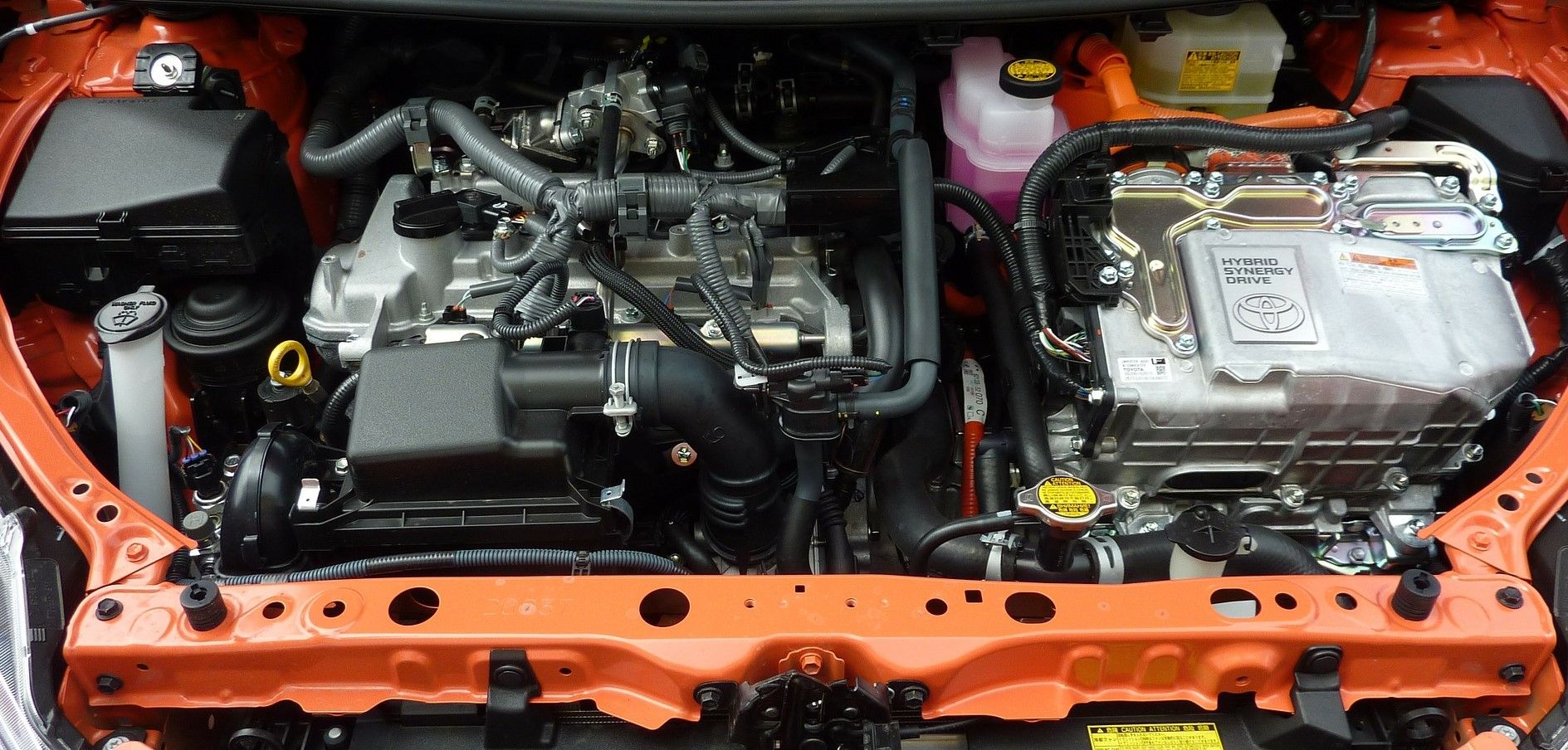

The coronavirus pandemic has brought the issue of dependency on Chinese suppliers to the fore. Manufacturers are now looking to ensure that their raw material supply chains remain stable throughout future unseen events. To do this requires diversity of suppliers, but to understand how this can be achieved in the rare earths market, it is necessary to look at the Japanese experience following China’s political threat to shutdown supplies in 2010.

Besides causing the price spike, the threat brought action from the Japanese government to help form a collaboration between Jogmec [Japan Oil Gas and Metals National Corporation] and Lynas. This resulted in the founding of the first mine at Mt Weld in Western Australia in 2011. A concentration unit was then established in 2012, followed by rare earth oxide production in Malaysia in 2013.

While the funding and technical developments were not easy, the reward of a fixed supplier is paying dividends, and is part of the ethos of Japanese business culture.

As Lynas' vice-president of sales and marketing, Pol Le Roux, explains, “[The Japanese] … take a different approach to the supply chain. They put a higher value on stability of supply. Let's say you are one of the top magnet makers in Japan, your customers in automotive and other industries will support your business when prices are low like they are today to ease the financial pain. But if prices spike, your Japanese customer will expect you to support him in the same way they supported you in difficult times. So, it is quite different to the western business model.”

However, while the Lynas project and supply chain is unique, it only solves half of the problem. It only supplies certain rare earths – all of them light metals.

Heavy metals, for example dysprosium and terbium oxide, are needed for the manufacture of magnetic motors found in, among other things, electric cars and nuclear-reactor control rods.

With a predicted 1 billion electric cars required by 2030 (just over half of all vehicles), stable and secure supplies of heavy rare earths will be vital for Western industry.

As Le Roux notes, “Today, there is no commercial separation of heavy rare earths outside China and several years ago we began to look at this opportunity. After all, we are already the only large separator of light rare earths outside China. Our Mt Weld deposit in Australia is basically a light rare earth resource, but it also has some dysprosium and terbium and there will be more when we start to exploit the Duncan deposit nearby. Today, we produce a small amount of heavy rare earth concentrate.”

In response, Lynas has teamed up with Texas-based rare earth compound producer Blue Line to build a heavy rare earth separation plant in Hondo, Texas. Full-scale production is expected in 2023.

Action like this shows that it is possible for the West to enter the rare earths processing market. It is perhaps the first step in the rethink of how specialist raw materials are sourced, with businesses reassessing the importance of supply chain diversity.

Consequently, raw material suppliers may expect changes in the rare earth element market sooner rather than later.

To find out more about how rare earth element extraction and processing may be ‘reshored’ to the West, read: The New Normal for the Rare Earth Element Market

Photo credit: Davgood Kirshot from Pixabay, Tom Fisk from Pexels, Pixabay, & Khusen Rustamov from Pixabay