Surfactants, while not widely known, can be found in almost every household on the planet.

They are the chemical cleaning agents which help remove dirt and grime, aid the mixing of water and detergent, and even help to breakdown surface tension - allowing the water to make better contact with whatever is being cleaned. This means that they literally make water wetter.

The problem is that they are largely produced with fossil fuels, meaning that they add to mankind’s impact on climate change. Furthermore, some cleaners, such as those used on cars or windows, may wash directly into rivers and streams, polluting natural waterways with the hard-to-breakdown petrochemicals.

To solve this problem, chemical researchers have developed a process which can industrially produce surfactants manufactured from renewable raw materials grown in Europe.

Called rhamnolipids, they are a new bio-surfactant which performs to the same standard as petroleum-based surfactants, yet require no petrochemical inputs – only natural sugars.

This process is now reaching commercial production with a new multimillion-euro investment by Evonik at its Slovenská Ľupča facility in Slovakia.

The biosurfactant breakthrough was made through a clever use of two natural components – one of sugar and the other a fatty acid.

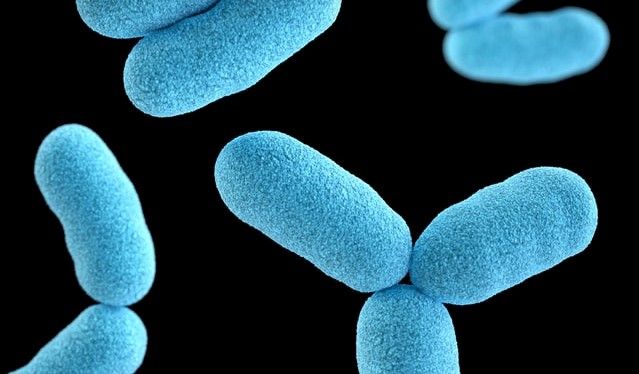

These were made from a fermentation process powered by a special strain of bacteria.

Previous efforts to produce surfactants from natural sugars had been successful in avoiding petrochemical inputs, but had required sugars from tropical climates. Importing such exotic feedstocks had added their own carbon footprint. Conversely, this new process uses sugars from European-grown corn.

Yet producing a chemical agent with a low environmental impact is only part of the challenge, as modern chemicals must be easy to recycle or breakdown – especially those designed for domestic use, such as soaps and shampoos which will be washed away after use.

“In the end, it goes down the drain and to the sewage treatment plant,” says Dr. Hans Henning Wenk, the head of Research and Development at Evonik Care Solutions. “In some regions, it is even released directly into the environment.”

This is why rhamnolipids, which are much less toxic than conventional surfactants and biodegrade very easily, are proving to be such a practical industrial chemical – especially when produced by the ‘safety strain’ of bacteria called Pseudomonas putida.

While other natural bacteria can convert fat into rhamnolipids, they typically do so very slowly or in very small amounts. Pseudomonas putida, meanwhile, has been modified to make rhamnolipids on an industrial scale.

“After we gave it the genetic tools to produce rhamnolipids in large amounts, we continuously optimized it further,” says Wenk. “To achieve this, we got bioengineers together with process experts, chemists, and engineers. We benefited here from our experience with the development of surfactants.”

It was this teamwork that solved the first major problem – rhamnolipids created too much foam.

“The expertise of a physical chemist proved to be crucial,” explains the Evonik website, “because he was able to explain why a surfactant that had some of its parameters modified suddenly behaved completely differently than before.”

The result is a cleaning agent which scores 100% on the Renewable Carbon Index (RCI), and also meets the requirements of OECD 301 F and EN ISO 11734 for rapid biodegradability under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions.

It is neutral enough in taste to be used in toothpaste, mild enough to be used on the skin, safe enough to be poured down the drain, but with a cleaning power sufficiently strong to be used in industrial cleaners.

Rhamnolipids are suitable for use in shampoos, washing up liquid, bath additives, facial cleansers, shower gels, and child-friendly soaps. It is also being embraced by major brands of household cleansers, such as Unilever, who value it as a key part of their goal to stop using fossil carbon in its household and textile care formulations by 2030.

The biosurfactants being produced by Evonik at its Slovenská Ľupča facility in Slovakia are the future of a chemical industry based on renewable raw materials.

Photo credit: CDC on Unsplash, Erik McLean, Anna Shvets on pexels, & Anna Shvets