When researchers from Stanford University discovered in 2015 that mealworms could eat plastic is was believed that it could provide a solution to the global plastic waste problem. But the breakthrough has yet to make a real impact on plastic waste as there is no profit in converting plastic particles into worms.

This is due to concerns about how much of the chemicals in plastic were consumed by the mealworms, and if they would accumulate over time.

However, a new Stanford study has now found that yellow mealworms can digest polystyrene (Styrofoam) containing a common toxic chemical additive and still be safely included in the food chain as a protein-rich feed for animals. Proof that value can be obtained from plastic waste.

“It's amazing that mealworms can eat a chemical additive without it building up in their body over time,” said Anja Malawi Brandon, a PhD candidate in civil and environmental engineering at Stanford and the study’s lead author. “This is definitely not what we expected to see.”

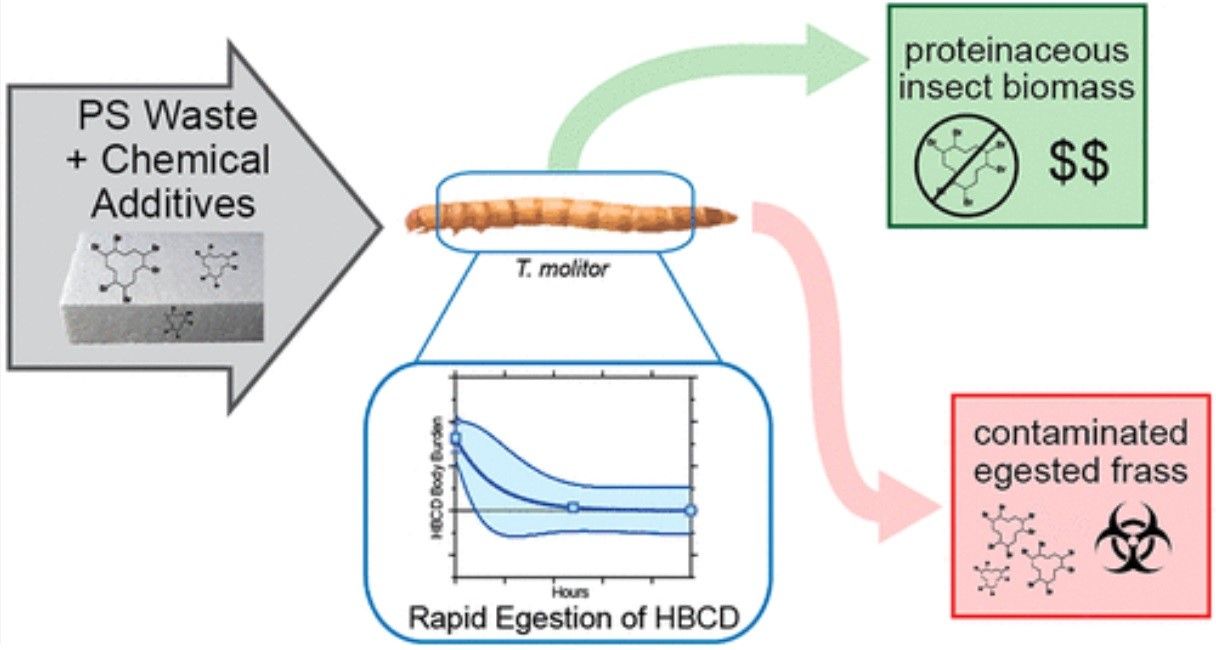

The researchers have now published their findings in the journal Environmental Science and Technology, where they explain, “… the fate of the flame retardant hexabromocyclododecane (HBCD) in polystyrene (PS)-degrading mealworms and in mealworm-fed shrimp.”

Where they found that, “In mealworms fed polystyrene containing high HBCD [fire retardant chemical] levels, only 0.27 ± 0.10%, of the ingested HBCD remained in the mealworm body tissue. This value did not increase over the course of the experiment, indicating little or no bioaccumulation.”

They also found no evidence of trophic level bioaccumulation or toxicity when the mealworms were fed to Pacific whiteleg shrimp. Making polystyrene a potential raw material for insect feed intended for the food chain.

The study was based on Styrofoam (polystyrene) as it is a common plastic, widely used for packaging and insulation, and yet expensive to recycle due to its bulk and low density. For this reason, large amounts of polystyrene are burnt or buried instead of being recovered. In addition to this, Styrofoam was a good study candidate as it often contains a flame retardant called hexabromocyclododecane (HBCD).

Chemicals such as HBCD are often used to decrease flammability in numerous types of plastic. In fact, the study notes that, “In 2015 alone, nearly 25 million metric tons of these chemicals were added to plastics.”

Yet HBCD can be highly toxic, causing “significant health and environmental impacts, ranging from endocrine disruption to neurotoxicity.” Consequently, the EU has plans to ban its use, while the US EPA is evaluating its risk.

Despite the potential health risks to the worms from eating such chemicals, the study found no negative effect or build-up of toxicity, giving them the potential to enter the food chain as animal feed.

“This work provides an answer to many people who asked us whether it is safe to feed animals with mealworms that ate Styrofoam,” said co-author Wei-Min Wu, a senior research engineer and expert in plastic-eating worms.

Instead of staying in the worms, the chemicals leave their bodies in their frass (excrement) – about 90% within 24 hours of consumption and 99.9% within 48 hours. Although, from here it would need treating.

As the Stanford University press release notes, “The researchers acknowledge that mealworm-excreted HBCD still poses a hazard, and that other common plastic additives may have different fates within plastic-degrading mealworms.”

At the same time, they understand that “mealworm-derived solutions to the world's plastic waste crisis” will never be long term solutions, and instead believe that biodegradable plastics and reducing the number of single-use products is the way forward.

“This is a wake-up call,” said Brandon. “It reminds us that we need to think about what we're adding to our plastics and how we deal with it.”

However, the team remain hopeful that their discovery could be a major boost to the agricultural industry, solving both the problem of plastic and easing the pressure on the supply of raw materials for animal feed.

You can watch a video explaining the breakthrough on YouTube.

If you wish to learn more about the raw materials for the animal feed industry, then you may want to read Rising Feed-Grade Phosphate Demand keeps Phosphate Miners Hunting or Three Tips for the Feed Additive Industry from Nutreco’s CEO.

Photo credit: Stanford