With the war between Russia and Ukraine now continuing for more than six months, fears are growing over its long-term impact.

Beyond the human toll being faced by those fighting or living near the conflict zone, politicians, businesspeople, and economists are increasingly concerned over the rising costs for basic raw materials.

For many households in Europe, the rising cost of energy (and especially gas for heating) is causing governments to consider extreme and expensive bailouts. Support for both consumers, businesses, and for failing energy companies. Energy rationing or random blackouts are also a possibility over the coming months.

But how will industry cope with the shortages of not only energy, but many of the basic raw materials needed to make anything?

Germany is often highlighted as the poster child of the precarious relationship between European economies and Russian foreign policy. Its booming chemical industry depends on gas for 30% of its output and 44% for its energy consumption.

While changes are being made to import gas from other regions, reduce consumption, and stock up on supplies for the coming winter, business leaders are nevertheless cautious about the future. This is evident in a recent study conducted by the Munich-based Institute for Economic Research which found that, “Business expectations fell to minus 44.4 points in July, compared to plus 11.8 points in the same month in 2021.”

And Germany is not alone in experiencing supply issues, as Mirabaud equity analyst William Mileham stated in a recent Reuters report, “European Chemical companies have had a bit of a torrid time. There have been production stoppages, and discussions around potential gas rationing have hit their share prices hard recently.”

The situation is very volatile, particularly for chemical products dependent on natural gas as no one can predict how badly supply from Russia will be disrupted.

For example, BASF issued a statement in early September acknowledging that, "[the company] is monitoring the situation and will decide, depending on the situation, on any changes to the production value chain as appropriate."

The hardest hit chemical product is the output for ammonia, with BASF already warning that, “some lines of production could be subject to output cuts, [including] syngas, a mixture of carbon monoxide and hydrogen, and the basic petrochemical acetylene.”

Reuters also reported that, “Rival ammonia makers Yara and CF Industries said last month they were slashing ammonia production in Europe due to soaring gas prices.”

Alongside being used as a fertilizer feedstock, ammonia is also used in the processing of meat and in the production of soft drinks.

However, beyond disruption to natural gas and other petroleum-based supplies, the sourcing of basic raw materials from Russia is also under pressure.

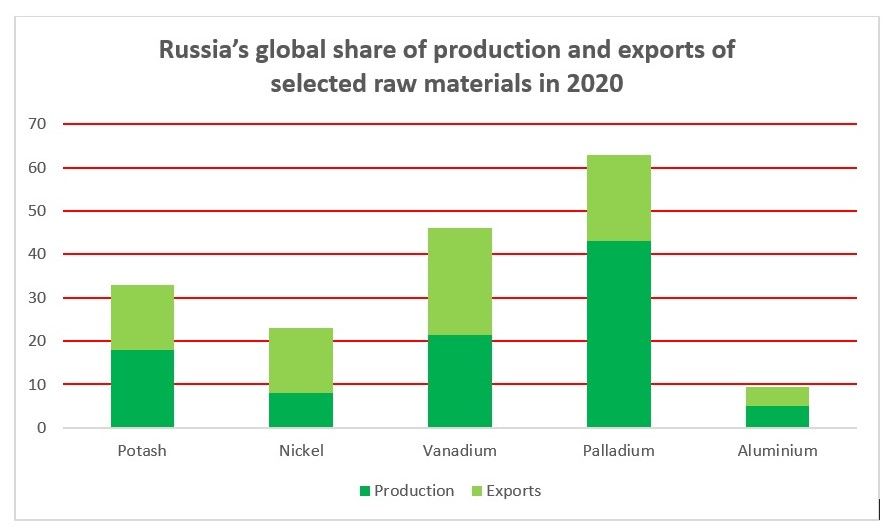

A recent report by the OECD highlights how disruption to the supply of wheat and other grains from both Ukraine and Russia is a major threat to populations in a number of developing countries. The shortage of such basic food stuffs will be further exacerbated by restrictions to exports of potash. Russia maintains 18% of global potash production and 15% of global potash exports, while Belarus has 17% and 20% respectively. The majority of potash is destined for fertilizer production.

Further raw material shortages are being felt in metal markets, with Ukraine and Russia being major exporters of the following:

Aluminium

Russia accounts for 5.5% of world aluminium production which is widely used in the automobile and aerospace industries, as well as in construction, the power sector, and also food and beverage packaging. Aluminium also makes up more than 85% of solar photovoltaic components, particularly in constructing the frames.

Nickel

Used to make stainless steel and alloys for construction, transport, and medical equipment. It is an essential material in the growing magnet industry, as well in the production of electronic devices, power generators, and batteries for electric vehicles.

According to the OECD, “Russia holds 11% of global nickel production and 15% of world nickel exports. It is a major supplier of nickel to Finland with an 84% import share. It also exports nickel to the Netherlands, Ukraine, and China, with 34%, 23%, and 13% import shares, respectively.”

Palladium

Applications include the manufacture of catalytic converters and in capacitors that store energy in electronic devices, as well as in jewellery and the dental care sector.

“Russia accounts for 43% of global palladium production and 21% of world palladium exports. Many countries depend on Russia for a substantial share of their palladium imports, among them Japan (43%), United States (37%), United Kingdom (30.5%), China (28.5%), Italy (26%), Germany (21%), and Korea (20%).”

Vanadium

This rare earth metal is used to improve the stability and corrosion resistance of steel alloys for applications in space vehicles, nuclear reactors, and airplanes. Vanadium alloys can also be employed in superconducting magnets.

“Russia accounts for 21% of global vanadium oxides production and 25% of world vanadium oxides exports.”

Resolving these supply chain issues will be far from easy, especially with the war still raging and winter approaching. The level of sanctions and the smooth passage of transport ships through the Black Sea may also vary as the military strategies and economics of the situation change.

However, the fundamental causes are evident and unlikely to change unless the free flow of trade is restored. As the OECD report clarifies, “These supply chain vulnerabilities are the result of export restrictions, bilateral dependencies, a lack of transparency and persistent market asymmetries, including the concentration of production in just a few countries.”

European economies will survive the coming winter. However, unless the war ends soon, manufacturers, raw material suppliers, and consumers everywhere will have to restrict production, manage a shortfall in supply, or simply do without.

Photo credit: Ron Lach at pexels, Jeremy Bazanger on Unsplash, Kwon Junho, Christian Chen, Ian Taylor, & Evgeny Karchevsky.